Karp–Lipton theorem

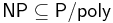

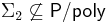

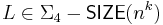

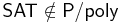

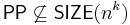

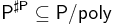

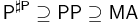

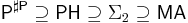

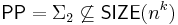

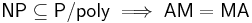

In complexity theory, the Karp–Lipton theorem states that if the boolean satisfiability problem (SAT) can be solved by Boolean circuits with a polynomial number of logic gates, then

and therefore

and therefore

That is, if we assume that NP, the class of nondeterministic polynomial time problems, can be contained in the non-uniform polynomial time complexity class P/poly, then this assumption implies the collapse of the polynomial hierarchy at its second level. Such a collapse is believed unlikely, so the theorem is generally viewed by complexity theorists as evidence for the nonexistence of polynomial size circuits for SAT or for other NP-complete problems. A proof that such circuits do not exist would imply that P ≠ NP. As P/poly contains all problems solvable in randomized polynomial time (Adleman's theorem), the Karp–Lipton theorem is also evidence that the use of randomization does not lead to polynomial time algorithms for NP-complete problems.

The Karp–Lipton theorem is named after Richard M. Karp and Richard J. Lipton, who first proved it in 1980. (Their original proof was initially collapsing PH to  , but Michael Sipser improved it to

, but Michael Sipser improved it to  .)

.)

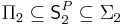

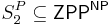

Variants of the theorem state that, under the same assumption, MA = AM, and PH collapses to SP

2 complexity class. There are stronger conclusions possible if PSPACE, or some other complexity classes are assumed to have polynomial-sized circuits. See P/poly. If NP is assumed to be a subset of BPP (which is a subset of P/poly), then polynomial hierarchy collapses to BPP.[1] If coNP is assumed to be subset of NP/poly, then the polynomial hierarchy collapses to third level.

Contents |

Intuition

Suppose that polynomial sized circuits for SAT not only exist, but also that they could be constructed by a polynomial time algorithm. Then this supposition implies that SAT itself could be solved by a polynomial time algorithm that constructs the circuit and then applies it. That is, efficiently constructable circuits for SAT would lead to a stronger collapse, P = NP.

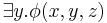

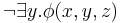

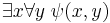

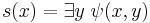

The assumption of the Karp–Lipton theorem, that these circuits exist, is weaker. But it is still possible for an algorithm in the complexity class  to guess a correct circuit for SAT. The complexity class

to guess a correct circuit for SAT. The complexity class  describes problems of the form

describes problems of the form

where  is any polynomial-time computable predicate. The existential power of the first quantifier in this predicate can be used to guess a correct circuit for SAT, and the universal power of the second quantifier can be used to verify that the circuit is correct. Once this circuit is guessed and verified, the algorithm in class

is any polynomial-time computable predicate. The existential power of the first quantifier in this predicate can be used to guess a correct circuit for SAT, and the universal power of the second quantifier can be used to verify that the circuit is correct. Once this circuit is guessed and verified, the algorithm in class  can use it as a subroutine for solving other problems.

can use it as a subroutine for solving other problems.

Self-reducibility

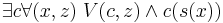

To understand the Karp–Lipton proof in more detail, we consider the problem of testing whether a circuit c is a correct circuit for solving SAT instances of a given size, and show that this circuit testing problem belongs to  . That is, there exists a polynomial time computable predicate V such that c is a correct circuit if and only if, for all polynomially-bounded z, V(c,z) is true.

. That is, there exists a polynomial time computable predicate V such that c is a correct circuit if and only if, for all polynomially-bounded z, V(c,z) is true.

The circuit c is a correct circuit for SAT if it satisfies two properties:

- For every pair (s,x) where s is an instance of SAT and x is a solution to the instance, c(s) must be true

- For every instance s of SAT for which c(s) is true, s must be solvable.

The first of these two properties is already in the form of problems in class  . To verify the second property, we use the self-reducibility property of SAT.

. To verify the second property, we use the self-reducibility property of SAT.

Self-reducibility describes the phenomenon that, if we can quickly test whether a SAT instance is solvable, we can almost as quickly find an explicit solution to the instance. To find a solution to an instance s, choose one of the Boolean variables x that is input to s, and make two smaller instances s0 and s1 where si denotes the formula formed by replacing x with the constant i. Once these two smaller instances have been constructed, apply the test for solvability to each of them. If one of these two tests returns that the smaller instance is satisfiable, continue solving that instance until a complete solution has been derived.

To use self-reducibility to check the second property of a correct circuit for SAT, we rewrite it as follows:

- For every instance s of SAT for which c(s) is true, the self-reduction procedure described above finds a valid solution to s.

Thus, we can test in  whether c is a valid circuit for solving SAT.

whether c is a valid circuit for solving SAT.

see Random self-reducibility for more information

Proof of Karp–Lipton theorem

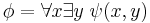

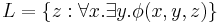

The Karp–Lipton theorem can be restated as a result about Boolean formulas with polynomially-bounded quantifiers. Problems in  are described by formulas of this type, with the syntax

are described by formulas of this type, with the syntax

where  is a polynomial-time computable predicate. The Karp–Lipton theorem states that this type of formula can be transformed in polynomial time into an equivalent formula in which the quantifiers appear in the opposite order; such a formula belongs to

is a polynomial-time computable predicate. The Karp–Lipton theorem states that this type of formula can be transformed in polynomial time into an equivalent formula in which the quantifiers appear in the opposite order; such a formula belongs to  . Note that the subformula

. Note that the subformula

is an instance of SAT. That is, if c is a valid circuit for SAT, then this subformula is equivalent to the unquantified formula c(s(x)). Therefore, the full formula for  is equivalent (under the assumption that a valid circuit c exists) to the formula

is equivalent (under the assumption that a valid circuit c exists) to the formula

where V is the formula used to verify that c really is a valid circuit using self-reducibility, as described above. This equivalent formula has its quantifiers in the opposite order, as desired. Therefore, the Karp–Lipton assumption allows us to transpose the order of existential and universal quantifiers in formulas of this type, showing that  Repeating the transposition allows formulas with deeper nesting to be simplified to a form in which they have a single existential quantifier followed by a single universal quantifier, showing that

Repeating the transposition allows formulas with deeper nesting to be simplified to a form in which they have a single existential quantifier followed by a single universal quantifier, showing that

Another proof and S2P

Assume  . Thefore, there exists a family of circuits

. Thefore, there exists a family of circuits  that solves satisfability on input of length n. Using self-reducibility, there exists a family of circuits

that solves satisfability on input of length n. Using self-reducibility, there exists a family of circuits  which outputs a satisfying assignment on true instances.

which outputs a satisfying assignment on true instances.

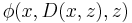

Suppose L is a  set

set

Since  can be considered an instance of SAT (by Cook-Levin theorem), there exists a circuit

can be considered an instance of SAT (by Cook-Levin theorem), there exists a circuit  , depending on

, depending on  , such that the formula defining L is equivalent to

, such that the formula defining L is equivalent to

-

(

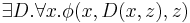

Futhermore, the circuit can be guessed with existential quantification:

-

(

Obviously (1) implies (2). If (1) is false, then  . In this case, no circuit D can output an assignment making

. In this case, no circuit D can output an assignment making  true.

true.

The proof has shown that a  set

set  is in

is in  .

.

What more, if the  formula is true, then the circuit D will work against any x. If the

formula is true, then the circuit D will work against any x. If the  formula is false, then x making the formula (1) false will work against any circuit. This property means a stronger collapse, namely to SP

formula is false, then x making the formula (1) false will work against any circuit. This property means a stronger collapse, namely to SP

2 complexity class (i.e.  ). It was observed by Sengupta.[2]

). It was observed by Sengupta.[2]

AM = MA

A modification[3] of the above proof yields

(see Arthur–Merlin protocol).

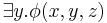

Suppose that L is in AM, i.e.:

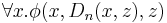

and as previously rewrite  using the circuit

using the circuit  that outputs a satisfying assignment if it exists:

that outputs a satisfying assignment if it exists:

Since  can be guessed:

can be guessed:

which proves  is in the smaller class MA.

is in the smaller class MA.

Application to circuit lower bounds – Kannan's theorem

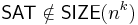

Kannan's theorem[4] states that for any fixed k there exists a language  in

in  , which is not in SIZE(nk) (This is a different statement than

, which is not in SIZE(nk) (This is a different statement than  , which is currently open and states that there exists a single language that is not in SIZE(nk) for any k). It is a simple circuit lower bound.

, which is currently open and states that there exists a single language that is not in SIZE(nk) for any k). It is a simple circuit lower bound.

Proof outline:

There exists a language  (the proof uses diagonalization technique). Consider two cases:

(the proof uses diagonalization technique). Consider two cases:

- If

then

then  and theorem is proved.

and theorem is proved. - If

, then by Karp–Lipton theorem,

, then by Karp–Lipton theorem,  and therefore

and therefore  .

.

A stronger version of Karp–Lipton theorem strengthens Kannan's theorem to: for any k, there exists a language  .

.

It is also known that PP is not contained in  , which was proved by Vinodchandran.[5] Proof:[6]

, which was proved by Vinodchandran.[5] Proof:[6]

- If

then

then  .

. - Otherwise,

. Since

. Since

-

(by property of MA)

(by property of MA) (by Toda's theorem and property of MA)

(by Toda's theorem and property of MA) (follows from assumption using interactive protocol for permanent, see P/poly)

(follows from assumption using interactive protocol for permanent, see P/poly)

- the containments are equalities and we get

by Kannan's theorem.

by Kannan's theorem.

References

- ^ S. Zachos, Probabilistic quantifiers and games, 1988

- ^ Jin Yi-Cai.

[1], section 6

[1], section 6 - ^ V. Arvind, J. Köbler, U. Schöning, R. Schuler, If NP has Polynomial-Size Circuits, then MA = AM

- ^ R. Kannan, Circuit-size lower bounds and non-reducibility to sparse sets

- ^ N. V. Vinodchandran, A note on the circuit complexity of PP

- ^ S. Aaronson, Oracles Are Subtle But Not Malicious

- Karp, R. M.; Lipton, R. J. (1980), "Some connections between nonuniform and uniform complexity classes", Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, pp. 302–309, doi:10.1145/800141.804678.

![z \in L \implies \Pr\nolimits_x[\exists y. \phi(x,y,z)] \geq \tfrac{2}{3}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f15f31e25f4c8e8cf7a3586694a8bd05.png)

![z \notin L \implies \Pr\nolimits_x[\exists y. \phi(x,y,z)] \leq \tfrac{1}{3}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c1ca488ab326dd4041ba633c2f021343.png)

![z \in L \implies \Pr\nolimits_x[\phi(x,D_n(x,z),z)] \geq \tfrac{2}{3}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/145e8a9cf3e1e8a3734387d990bec51e.png)

![z \notin L \implies \Pr\nolimits_x[\phi(x,D_n(x,z),z)] \leq \tfrac{1}{3}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ae4447292c13b5ecf2225b47411d3eac.png)

![z \in L \implies \exists D. \Pr\nolimits_x[\phi(x,D(x,z),z)] \geq \tfrac{2}{3}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d5e7ab30f921f5b01441e452b84b0213.png)

![z \notin L \implies \forall D. \Pr\nolimits_x[\phi(x,D(x,z),z)] \leq \tfrac{1}{3}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4a6d919a71cd38bbf0e669de43238dce.png)